Sea Lions

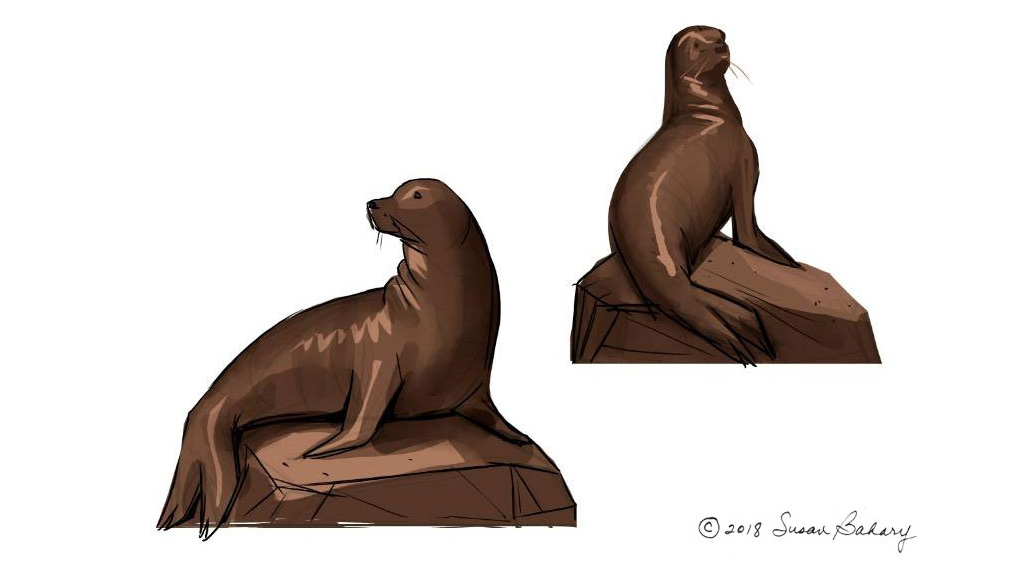

The sculpture of the Sea Lion at the National Service Animals Memorial represents the California Sea Lions used by the Navy to find and retrieve equipment lost at sea and to identify intruders swimming into restricted areas.

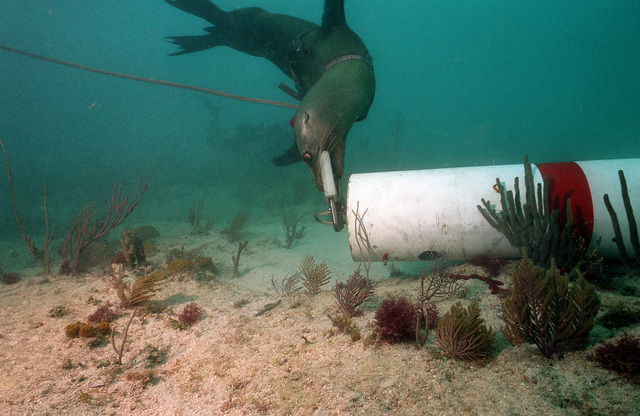

A sea lion swims to the ocean floor to hook up a retrieving line to practice ordnance. The sea lion is being trained by Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) Mobile Unit Four, which also trains dolphins to retrieve underwater ordnance

A marine mammal handler from the Navy Marine Mammal Program prepares to send Cody, a California sea lion, into the water during the International Mine Countermeasures Exercise (IMCMEX).

Sea lions, with their excellent eyesight, are used by the U.S. Navy to find and retrieve unarmed test ordinances like practice mines. Handlers give a sea lion an attachment system it can hold in its mouth and send the mammal overboard. Once the animal finds its target, it clamps the device to it and handlers in a boat at the surface can bring the object in.

A 2011 media demonstration in San Diego Bay, California, featured a former U.S. Navy SEAL attempting to infiltrate the harbor with an unarmed mine. The Navy deployed dolphins and sea lions to patrol the area, and both caught the diver on every one of his five attempts. The sea lion even managed to attach a clamp to the diver’s leg, and handlers on the surface reeled him in like a fish.

Both California sea lions and bottlenose dolphins are fairly hardy, smart, and very trainable. Sea lions also have the advantage of being amphibious. That’s why the U.S. Navy ended up using them instead of other marine mammals.

The U.S. military is experimenting with trained sea lions as a way of providing security for the huge American port complex in Bahrain.

Sources say the Navy decided to acknowledge the experiment, at least in part, because the sea lions were making so much noise in their pens at Bahrain harbor, home of the Navy’s largest facility in the Persian Gulf.

Sea lions are not native to those waters and typically bark loudly when excited. There was no way their presence, officials decided, could be kept secret. No final decision has been made on whether the sea lions will stay.

The animals — along with dolphins and a beluga whale or two — are trained as part of the Navy’s Marine Mammal Program in San Diego. They are trained to hunt for mines, to locate objects lost in deep water and to provide harbor security.

Intelligence officials have warned repeatedly about the threat of terrorists using divers to blow up ships. That’s what both the sea lions and the dolphins are trained to deal with, among other things.

Working with human handlers, the sea lions are trained to locate unexpected swimming intruders, to snap a locking clamp on an arm or leg, then leave.

The clamp is connected to a rope and signal buoy that humans with guns would then reel up, presumably pulling up a human on the other end. In theory, the animals would not be hurt. Their contact with a potential terrorist — who would presumably be surprised — would last only an instant as they briefly made contact.

With a quarter of the world’s navys participating, including 6,500 sailors from every region, IMCMEX is the largest international naval exercise promoting maritime security and the free-flow of trade through mine countermeasure operations, maritime security operations and maritime infrastructure protection in the U.S. 5th Fleet area of responsibility and throughout the world. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Kathleen Gorby/Released

The Memorial

Education Program

Let's Build It!

Endorsements & Collaborations

Friends of NSAM

The Purple Poppy®

Contact Us

5662 Calle Real #105

Goleta, CA 93117

Email: info@NSAMproject.org

Phone: 202-774-1992

NSAM is a 501 (c)(3) non-profit organization.

EIN #27-4620979